Imagine your application as a bustling metropolis. The database schema? That's the city's infrastructure—its roads, utility lines, and building codes. Without a meticulously planned, robust infrastructure, traffic grinds to a halt, services fail, and growth becomes impossible. In the world of high-performance applications, advanced schema strategies and best practices aren't just good ideas; they're the bedrock upon which database scalability, efficiency, and long-term success are built.

Moving beyond basic table creation, this guide delves into the nuanced decisions and forward-thinking approaches that empower your database to handle exponential data growth, complex queries, and ever-evolving business demands. It���s about designing systems that not only work today but thrive tomorrow.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways for Robust Schema Design

- Prioritize Understanding: Begin by deeply analyzing data requirements and access patterns before writing a single line of DDL.

- Balance Normalization: Use normalization to reduce redundancy and ensure consistency, but strategically denormalize for read-heavy performance gains.

- Choose Keys Wisely: Opt for surrogate primary keys and use foreign keys to enforce referential integrity where performance allows.

- Optimize Data Types: Select the most precise data types to conserve storage and boost query speed.

- Strategic Indexing: Index frequently queried columns but avoid over-indexing, which can hinder write operations.

- Scale with Partitioning & Sharding: Distribute large datasets effectively using partitioning within a database and sharding across multiple instances.

- Future-Proof IDs: Employ scalable auto-incrementing strategies like UUIDs or Snowflake IDs for distributed environments.

- Integrate Caching: Reduce database load and latency with application-level or database query caching.

- Plan for Evolution: Implement tools and practices for seamless schema migrations and backward compatibility.

- Document & Govern: Maintain consistent naming conventions, comprehensive documentation, and audit trails for maintainability and trust.

The Foundation: Understanding Your Data and Its Destiny

Before you even think about tables and columns, the most advanced schema strategy begins with a whiteboard and a deep dive into your application's heart. Understanding data and access patterns is paramount. It’s the difference between building a highway system for a sleepy town versus a bustling metropolis.

Ask yourself:

- What data will this application store? What are its attributes, relationships, and lifecycle?

- How frequently will data be read versus written? (e.g., a blogging platform is read-heavy; an IoT data ingestion system is write-heavy).

- What types of queries will be most common? Simple lookups, complex joins, aggregations?

- Which columns will be frequently used in

WHERE,JOIN, orORDER BYclauses? - How fast will the data grow? Linear, exponential? What are the projected volumes over 1, 3, 5 years?

- What are the transaction and consistency requirements? Is eventual consistency acceptable, or do you need strong ACID guarantees?

This upfront analysis isn't just theory; it directly informs crucial decisions about your table structures, indexing strategies, and even whether a traditional relational database is the right fit. It’s the lens through which every subsequent decision should be viewed.

The Normalization vs. Denormalization Tightrope Walk

One of the most foundational decisions in schema design revolves around normalization and denormalization. It's a classic trade-off between data integrity and query performance.

Embracing Normalization (When to Go 3NF or Beyond)

Normalization is the process of organizing the columns and tables of a relational database to minimize data redundancy and improve data integrity. The goal is often to reach the Third Normal Form (3NF), where:

- All non-key attributes are dependent on the primary key.

- No non-key attribute is dependent on another non-key attribute.

Benefits of Normalization:

- Reduced Data Redundancy: Less storage space and fewer inconsistencies.

- Improved Data Quality: Changes to data only need to be made in one place.

- Easier Maintenance: Simpler updates, inserts, and deletes.

- Enhanced Data Integrity: Helps prevent update anomalies.

When to Normalize:

Normalization is ideal for OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) systems, where data integrity, transactional consistency, and frequent updates are critical. Think banking systems, inventory management, or CRM platforms.

Strategic Denormalization (When Speed Trumps Strict Purity)

While normalization is powerful for data integrity, it can lead to complex queries involving many JOIN operations, which can degrade performance, especially in read-heavy applications. Denormalization introduces controlled redundancy into a schema to improve read performance.

Benefits of Denormalization:

- Faster Read Queries: Fewer joins mean quicker data retrieval.

- Simpler Queries: Querying becomes less complex, reducing development time.

- Optimized for Reporting: Great for OLAP (Online Analytical Processing) systems or dashboards where aggregated data is frequently accessed.

When to Denormalize:

Consider denormalization for read-heavy workloads or specific use cases where query performance is paramount and the overhead of maintaining redundant data is acceptable. Common strategies include: - Adding redundant columns: Duplicating a frequently accessed column from a related table into a primary table.

- Pre-joining tables: Creating a table that is a permanent join of two or more tables.

- Storing aggregate data: Keeping summary data (e.g., total sales for a month) directly in a table rather than recalculating it on the fly.

The Hybrid Approach: Best of Both Worlds

For most complex applications, a hybrid approach is often optimal. Start with a normalized design to ensure data integrity, then strategically denormalize specific tables or create materialized views for performance-critical read operations. This ensures a solid foundation while delivering the speed your users demand.

Keys and Constraints: The Rules of Engagement

The backbone of any relational schema lies in its keys and constraints. They define relationships and enforce data integrity.

Primary Keys: Your Unique Identifiers

Every table needs a primary key (PK) to uniquely identify each row. This is non-negotiable. The choice between natural and surrogate keys is a critical one:

- Natural Keys: Derived from existing business data (e.g., Social Security Number, email address). While seemingly intuitive, natural keys can change (e.g., an email address), contain sensitive information, or be composite (multiple columns), complicating joins.

- Surrogate Keys: Artificial identifiers with no business meaning (e.g., an auto-incrementing integer, UUID). These are generally preferred for primary keys because they are stable, typically single-column, and efficient for joins.

Best Practice: Favor surrogate keys (like an auto-incrementing integer) for primary keys. They are simpler, more stable, and provide better performance characteristics for indexing and joins.

Foreign Keys and Constraints: Maintaining Order

Foreign keys (FKs) are crucial for establishing and enforcing referential integrity between tables. They ensure that a value in a dependent table's FK column matches a value in the parent table's PK column, preventing "orphaned" records (e.g., an order referencing a non-existent customer).

Benefits of Foreign Keys:

- Referential Integrity: Guarantees valid relationships between tables.

- Data Consistency: Prevents accidental data corruption.

- Schema Clarity: Makes relationships explicit and easier to understand.

Trade-offs and Considerations: - Write Overhead: Foreign key constraints add overhead to

INSERT,UPDATE, andDELETEoperations as the database must check referential integrity. - Bulk Data Loading: Can complicate and slow down large-scale data imports, often requiring disabling constraints temporarily.

- Distributed Systems: In microservices architectures or highly distributed databases, enforcing referential integrity at the database level might be challenging or counterproductive. Here, application-enforced integrity checks might be a more flexible approach, though they shift the burden to developers.

Beyond FKs: Use other constraints and validation rules (e.g.,NOT NULL,UNIQUE,CHECKconstraints) to enforce data integrity directly at the database level. For instance, aCHECKconstraint can ensure apricecolumn is always positive, or aUNIQUEconstraint can prevent duplicate email addresses.

Data Types: The Right Fit for Every Value

Choosing the appropriate data types for your columns is a small decision with significant long-term impact on storage, performance, and data integrity.

- Storage Optimization: Using

INTinstead ofBIGINTwhen numbers won't exceed theINTrange saves disk space. Similarly,VARCHAR(255)is more efficient thanTEXTif you know the maximum length of a string. - Performance: Queries on smaller data types are generally faster. Integer comparisons are quicker than string comparisons.

- Data Integrity: A

DATEtype correctly stores dates and prevents invalid date entries, while aVARCHARwould allow anything. - Time Zones: Use

TIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONE(or similar, depending on your database) overDATETIMEif your application handles users across different time zones.TIMESTAMPoften stores time in UTC, which is generally a best practice for global applications.

Avoid NULLs When Possible: WhileNULLindicates missing or unknown data, extensive use can complicate indexing, add storage overhead, and lead to more complex queries (e.g.,IS NULLvs.= NULL). If a column always should have a value, declare itNOT NULL.

Indexing Strategies: Turbocharging Your Queries

Indexes are like the index in a book: they help the database quickly locate specific rows without scanning the entire table. While essential for performance, they come with trade-offs.

Types of Indexes and When to Use Them:

- Primary Key Indexes: Automatically created on your primary key, enforcing uniqueness and providing fast lookups.

- Composite Indexes: Cover multiple columns (

CREATE INDEX idx_name ON table_name (col1, col2)). Ideal for queries that frequently filter or sort by combinations of columns. The order of columns in a composite index matters! Place the most selective (most frequently filtered) column first. - Partial/Filtered Indexes: Index only a subset of rows that meet a specific condition (e.g.,

CREATE INDEX idx_active_users ON users (email) WHERE status = 'active'). Useful for very large tables where only a small fraction of rows are actively queried. - Covering Indexes: An index that includes all the columns needed to satisfy a query, meaning the database doesn't need to access the actual table data. This can dramatically speed up queries.

Best Practices and Pitfalls:

- Index

WHERE,JOIN, andORDER BYColumns: These are the prime candidates for indexing. - Avoid Over-indexing: Every index adds overhead to

INSERT,UPDATE, andDELETEoperations because the index itself must also be updated. Over-indexing can slow down write-heavy applications. - Monitor and Analyze: Use your database's performance monitoring tools to identify slow queries and determine if new indexes are needed or if existing ones are unused and can be dropped.

- Don't Index Everything: Columns with low cardinality (few unique values) are generally poor candidates for indexing unless they are used in very specific, filtered queries.

Scaling Data: Partitioning and Sharding

For datasets that grow to truly massive sizes (terabytes, petabytes), traditional indexing isn't enough. Partitioning and sharding are advanced strategies to distribute data, improving performance, manageability, and availability.

Partitioning: Dividing Within a Database

Partitioning splits a large table into smaller, more manageable logical pieces within a single database instance. To the application, it still looks like one table.

- Range Partitioning: Divides data based on a range of values (e.g.,

datecolumn,customer_idranges). Useful for time-series data or data with clear value boundaries. - Example: Sales data partitioned by year, allowing queries for a specific year to only scan that year's partition.

- List Partitioning: Splits data based on a predefined list of discrete values (e.g.,

regioncolumn,product_category). - Example: User data partitioned by geographic region (e.g., 'NA', 'EU', 'APAC').

- Hash Partitioning: Distributes data evenly across partitions using a hash function on a specified column. Good for achieving even distribution when there's no natural range or list.

- Example: User records distributed evenly by

user_idacross partitions.

Benefits of Partitioning: - Improved Query Performance: Queries often only need to scan a relevant subset of data.

- Easier Maintenance: Operations like

TRUNCATEorARCHIVEcan be applied to individual partitions. - Reduced Index Size: Indexes are often smaller and more efficient per partition.

Sharding: Spreading Across Databases

Sharding takes distribution a step further by splitting data across multiple independent database instances (shards). Each shard is a separate database. This is critical for scaling beyond the limits of a single machine.

- Key-Based (Hash) Sharding: Distributes rows based on a hash of a key (e.g.,

user_id,product_id). A consistent hashing algorithm determines which shard a record belongs to. - Example: User 1-1000 on Shard A, User 1001-2000 on Shard B.

- Range-Based Sharding: Allocates data to shards based on a range of values.

- Example: All users from California on Shard A, all from New York on Shard B. Can lead to "hot spots" if data isn't evenly distributed geographically or chronologically.

- Geographic Sharding: Separates data by physical location, improving localized performance and meeting data residency requirements.

Benefits of Sharding: - Massive Scalability: Overcomes single-server resource limitations.

- Increased Availability: Failure of one shard doesn't affect the entire system.

- Improved Performance: Queries against smaller, distributed datasets are faster.

Challenges of Sharding: - Increased Complexity: Harder to manage, query, and maintain.

- Cross-Shard Queries: Queries requiring data from multiple shards can be very complex and slow.

- Resharding: Rebalancing data when adding or removing shards is a significant operational challenge.

Scalable Auto-Incrementing Strategies

Standard auto-incrementing integer IDs are simple and effective for single-database systems. However, in distributed or sharded environments, they can become a bottleneck or lead to collisions.

- UUIDs (Universally Unique Identifiers): Globally unique 128-bit numbers. They are generated independently, making them ideal for distributed systems.

- Pros: No coordination needed, excellent for merging databases, truly unique.

- Cons: Larger storage, can lead to index fragmentation (due to their random nature), making some lookups slower. UUID v7 (or similar time-ordered UUIDs) can mitigate fragmentation.

- Snowflake IDs (e.g., Twitter’s Snowflake): A distributed ID generation system that produces unique, time-ordered 64-bit integers. These IDs combine a timestamp, a machine ID, and a sequence number.

- Pros: Globally unique, time-ordered (good for indexing), compact (64-bit), sortable.

- Cons: Requires a distributed ID generation service.

- Database Sequences: Many databases (like PostgreSQL) offer sequences as standalone objects that can generate unique numbers. These can be customized and, in some cases, configured for distributed environments.

- Hybrid Approach: Use UUIDs for public-facing IDs and internal auto-incrementing integers for internal joins within a single shard.

Caching: The Ultimate Performance Multiplier

Caching is a strategy to store frequently accessed data in a faster-access tier (usually memory) to reduce database load and improve response times. It's not strictly a schema strategy, but it's an essential advanced practice to ensure your schema performs optimally under load.

- Application-Level Caching: Storing data directly in your application's memory or a dedicated caching service (e.g., Redis, Memcached). This is often the most effective and flexible caching layer.

- Materialized Views: Precomputed query results stored as a database object. When complex reports or aggregations are run frequently but data doesn't change constantly, materialized views can drastically speed up queries by providing an immediate answer. They need to be refreshed periodically.

- Database Query Caching: Some databases offer internal query caches that store the results of frequently run queries. While useful, they can be invalidated often and are less flexible than application-level caching.

Best Practice: Implement caching at the application level for maximum control and performance. Design your schema with caching in mind, identifying data that is read often but updated infrequently.

Data Archiving and Retention: Decluttering for Speed

As data accumulates, old historical data can bloat tables, slow down queries, and increase storage costs. An advanced strategy involves robust data archiving and retention policies.

- Move Old Data: Regularly move historical data from active, high-performance tables to separate archive tables. These archive tables might reside in a different database, a data warehouse, or even cheaper storage like object storage (e.g., Amazon S3).

- Time-Series Databases: For specific types of historical data (e.g., sensor readings, logs), consider using specialized time-series databases which are optimized for ingesting and querying time-stamped data.

- Automated Policies: Implement automated cleanup and purging policies based on legal, compliance, and business requirements. Define how long different types of data must be retained and when it can be safely deleted or moved.

Archiving keeps your active datasets lean, improving the performance of daily operations and reducing backup/restore times.

Schema Evolution and Versioning: Adapting to Change

Applications rarely stand still. Business requirements change, features are added, and your schema must evolve. Seamless schema migration and versioning are critical for agile development and avoiding downtime.

- Database Migration Tools: Tools like Flyway or Liquibase manage schema changes by applying versioned scripts. They track which migrations have been applied, ensuring consistency across environments.

- Maintain Backward Compatibility: Whenever possible, schema changes should be backward-compatible.

- Adding nullable columns.

- Adding new tables.

- Renaming columns with aliases.

- Avoid: Renaming or dropping columns, changing data types in incompatible ways without a clear deprecation strategy and transition period.

- Blue-Green Deployments/Feature Flags: For major, potentially breaking schema changes, use deployment strategies like blue-green deployments (running two identical production environments) or feature flags to gradually roll out changes and quickly roll back if issues arise. This isolates the impact of schema changes.

Thinking about schema evolution from day one helps design a more flexible and adaptable database.

The Unsung Heroes: Naming, Documentation, and Audit Trails

These practices might seem less "advanced" but are absolutely critical for a maintainable, trustworthy, and collaborative schema.

Consistent Naming Conventions

Adopt and strictly adhere to a consistent naming convention for all database objects (tables, columns, indexes, constraints, views, stored procedures).

- Examples:

snake_casefor tables/columns (user_accounts,first_name), plural vs. singular table names (e.g.,usersvs.user), meaningful prefixes/suffixes for indexes (idx_users_email). - Benefits: Makes the schema intuitive, reduces cognitive load for developers, and simplifies writing queries.

Schema Documentation

A well-designed schema is only truly valuable if it's understood. Document your schema comprehensively.

- Comments in DDL Scripts: Use inline comments to explain the purpose of tables, columns, and complex constraints.

- Separate Documentation: Maintain external documentation (e.g., Confluence, internal wiki, dedicated schema documentation tools) that explains:

- Business context for tables/columns.

- Relationships between tables.

- Assumptions and design choices.

- Data ownership and lifecycle.

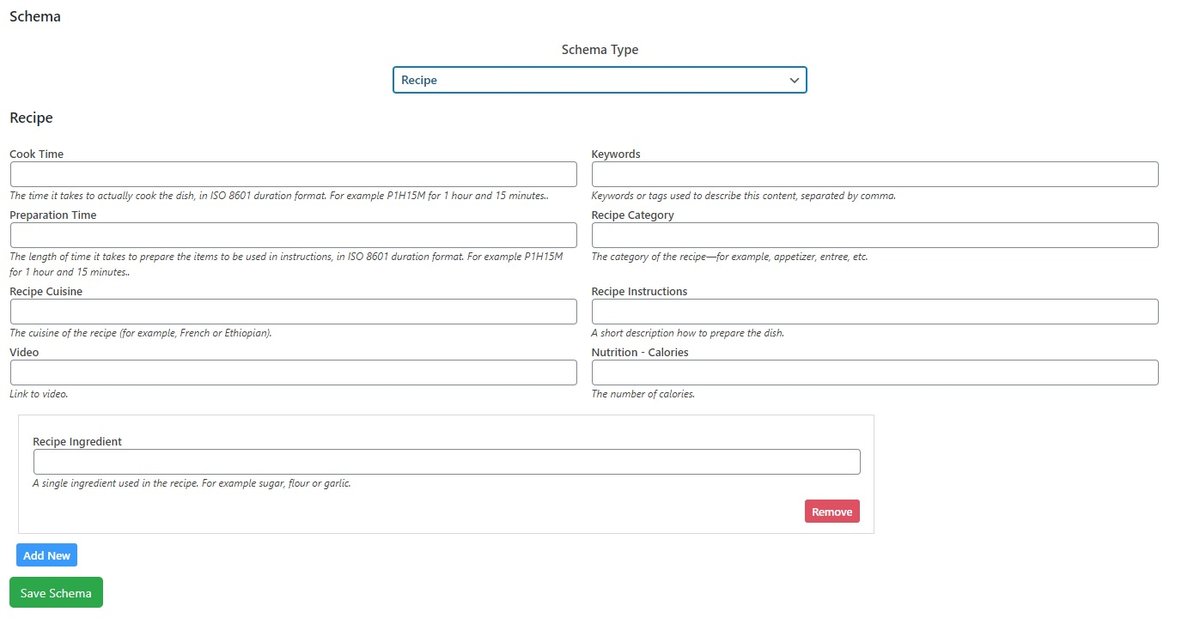

This vastly improves onboarding for new team members and helps prevent misinterpretations years down the line. It's also an excellent way to bridge the gap between technical implementation and business understanding. Speaking of structured data and understanding, ensuring your web content is also clearly defined for search engines can significantly impact discoverability. For assistance with crafting optimal structured data for your website, you might find Our schema markup generator to be a valuable resource.

Audit Trails

For sensitive data or applications requiring high accountability, implementing audit tables is a non-negotiable advanced strategy.

- Purpose: Track who made changes, what changed, when it changed, and from where.

- Implementation: Often involves trigger-based solutions or application-level logging that writes to dedicated audit tables.

- Benefits: Essential for compliance (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA), debugging, and ensuring data integrity.

Your Blueprint for Future-Proof Databases

Designing a scalable and efficient database schema is not a one-time event; it's an ongoing journey. By embracing these advanced schema strategies and best practices, you're not just building tables and columns; you're engineering a foundation that can withstand the test of time, accommodate unforeseen growth, and continuously deliver high performance.

Start with a deep understanding of your data and its usage. Strategically balance the theoretical purity of normalization with the practical demands of performance. Choose your keys, data types, and indexing strategies with precision. When the scale demands it, intelligently employ partitioning and sharding. And never underestimate the power of robust processes for schema evolution, clear documentation, and consistent governance.

The effort invested upfront in these advanced strategies pays dividends in reliability, maintainability, and the ability to unlock true database scalability for years to come. Your database isn't just a storage locker; it's the beating heart of your application, and a well-designed schema ensures it beats strong and true.